The Bison on Catalina Island Are in Poor Health – Unseen Research

Encountering bison in an unexpected place, such as Catalina Island, may draw visitors’ attention and boost the sale of related novelties, but this mismatched pairing hasn’t worked out so well for the bison.

Studies dating back to the 1970s have repeatedly documented limited forage, poor habitat conditions, and poor nutrition, health, and condition of the bison on Catalina Island. Markedly low reproductive rates, the persistence of open sores, reduced overall body size, poor blood profiles, and the frequent observation of emaciated individuals have all been reported.

In this article, I will outline the existing research, including a never-before-seen manuscript explaining why the bison on Catalina Island are in such poor health and what should be done.

Catalina Island Bison – A Brief Introduction

I have already written a post detailing the origin of the bison on Catalina Island, but here is a brief recap:

Fourteen bison were introduced to Catalina Island in 1924 in association with film production and left on the island after filming wrapped.

The herd was supplemented and permitted to grow, and at its peak, it expanded beyond 500 individuals. After its founding in 1972, the Catalina Island Conservancy became responsible for managing 88% of the island, including the bison.

It is important to note that the bison on Catalina Island are not wildlife; they are owned and managed as livestock. In the same way that ranchers are not permitted to neglect their cattle or let them starve, the Conservancy is responsible for the health and welfare of the bison.

Before 2010, the bison population on the island was managed through periodic removals and, since then, contraception. Despite these population managment efforts and the fact that the bison are trapped on the island, there is a desire to maintain the illusion of a wild and free bison herd.

Population Ecology & Ecological Effects of Bison on Catalina Island.

In 2002, the Conservancy commissioned a study to assess the population ecology and ecological effects of the bison on Catalina Island. Blood sampling, weight measurements, and dietary analysis were also conducted to assess the bison’s health.

As noted within the report, the phenology (timing and cyclical patterns) of grasses and herbaceous plants on Catalina Island is out of phase with the reproductive phase of female bison. High-quality nutrient-rich forage is only available during gestation, with grasses and herbaceous forage drying by late May and June during the energetically costly lactation period.

Bison and other mammals typically experience a doubling or tripling of dietary energy needs during lactation compared to nonreproductive individuals of the same species.

Sweitzer et al. – Our analysis of data on body size, blood chemistry, and hematology supports the hypothesis that bison on Catalina Island are experiencing nutritional stress related to asynchrony in plant phenology and the costs of reproduction.

Blood chemistry tests measure the amount of certain chemicals in the blood, including enzymes, electrolytes, fats, cholesterol, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), sugars, proteins, vitamins, and minerals.

Blood hematology tests assess the components of the blood, including white blood cell counts (WCB), red blood cell counts (RBC), platelets, hematocrit red blood cell volume (HCT), and hemoglobin concentration (HC), and are used to help diagnose anemia, certain blood cancers, and inflammatory disease.

American Bison in a Mismatched Environment – Unseen Manuscript

Multiple independent manuscripts were drafted from the data collected during the Sweitzer et al. 2003 study, including one titled American Bison in a Mismatched Environment: Implications for Species Introductions. Unfortunately, this manuscript was never published for reasons I will not get into here.

Bison on Catalina Island are significantly smaller in body mass than mainland bison occupying prairie and mountainous rangelands, likely due to nutritional stress. Among multiple blood chemistry and hematological parameters from October 2000 and 2002, cholesterol and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) values from cows tested suggest that bison on Catalina Island are malnourished compared to cattle and captive bison…

BUN levels were likely high because of insufficient energy intake and subsequent tissue catabolism…

Interestingly, female bison in 2002 had elevated levels of gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) and bilirubin, possibly due to ingestion of tall fescue infected by the fungus Neotyphodium coenophialum and/or ingestion of perennial ryegrass infected by the fungus Pithomyces chartarum. Infected fescue can result in ‘summer slump,’ which is reflected by decreased weight gain, a rough hair coat that does not seem to shed, and the tendency to stand in the shade or in water instead of eating.

Consumption of infected ryegrass may lead to photosensitization, which can produce lesions on areas of the body with sparse hair cover, as well as near the eyes and mouth. On average, the two species of grass combined comprise 8% of the monthly diet of bison on Catalina Island.

We frequently observed male and female bison with bloody sores on their hindquarters and periodically noted instances of cows with putrescent eyes during the course of the study. At least two bison cows have been euthanized since 1995 because of “bad eyes” (H. Saldaña, personal communication)…

The skewed adult sex ratio we noted is not an artifact of periodic culling to reduce herd sizes; similar numbers of males (787) and females (818) were removed from the island from 1969-2004. Rather, the female-biased sex ratio was likely attributable to lower survival in male bison. Mortality of young bison is typically low, although young males suffer higher mortality than young females, potentially because males are more susceptible to nutritional stress.

It has been hypothesized that nutritional stress results in asynchronous calving patterns. Although we estimated that upwards of 90% of the calves on the island were born from mid-April to early May, newborn calves were observed as early as March and as late as October. In the last 10 years, newborn bison calves have occasionally been observed in December on the Island…

The phenological asynchrony between maximum forage quality and calving/lactation is possibly a major determinant of the poor nutritional status of female bison on Catalina Island…

The trophic asynchrony observed on the island is exacerbated by the extremely poor quality of the Mediterranean grasses that make up the bulk of the bison diets. Once these annual grasses have matured, they are deficient in protein, vitamin A, and calcium, all of which are critical to lactating bovids.

American Bison in a Mismatched Environment: Implications for Species Introductions – Unpublished Manuscript.

Low Reproductive Rates in Catalina Island Bison

In his book American Bison: A Natural History and several other studies, behavioral ecologist Dr. Dale Lott, PhD., describes the reproductive behavior of American bison and highlights the contrast between the bison on Catalina Island and those present on the National Bison Range, where he was born.

In their research, Dr. Lott and his students noted that while 90% of mature cows on the National Bison Ranch gave birth each year, on Catalina, only about 30% annually gave birth. Resource scarcity was determined to be the underlying cause, but not in the way you might think.

On the National Bison Range, dominance in cows was associated with age until they reached full size at approximately three years old, and then dominant behaviors subsided. Two-year-olds dominated one-year-olds, and three-year-olds dominated two-year-olds, and size was not a factor. For instance, a three-year-old cow did not dominate a six-year-old cow, even if it was larger.

Bison cow hierarchy, or “buffalo cow society,” as Lott called it, was very different on Catalina Island. Using corral-based studies whereby the age and weight of each cow were known, hierarchy correlated perfectly with body weight. Every cow dominated every lighter cow, and every lighter cow was subordinate to every heavier cow.

After releasing the bison from the corrals and monitoring them for four years, Lott noted that the heaviest, most dominant cows calved yearly, and the lightest, most subordinate not at all.

According to Lott and his team, resource scarcity fueled competition on Catalina Island, and those unable to compete often went without. At the time of Lott’s research (1975), approximately 400 bison resided on Catalina Island, along with thousands of feral pigs, feral goats, and an introduced population of mule deer (the number was unknown at the time but had been estimated to be three thousand previously).

At the time of Sweitzer’s research (2001-2002), nearly all goats and pigs had been removed, the mule deer population was estimated to be around 600 individuals, and the bison herd ranged between 303 and 379 individuals. The island was said to be in a state of recovery, leading many people to assume that conditions for the bison had improved, yet the calving rate was recorded at a dismal 42%. Why might that be?

A recovering island means an increase in native trees and other woody plants and a decrease in the “suitable bison range.” As the habitat on the island improves for native species, it becomes less useful for the introduced bison, and as landscape engineers, the bison actively interfere with the recovery of the island.

Table 1. Estimated mean calving rates (% adult females with calves) for adult female bison on Catalina Island, California, and from various mainland herds of free-roaming or captive bison. These data and sources were compiled by Sweitzer et al. 2003.

| Location | Calving Rate | Female Age | Source |

| Captive-raised herds with adequate forage/supplementation | >95 | >3 | Lee 1990 |

| National Bison Range, MT | 82 | >3 | Rutberg 1986 |

| Theodore Roosevelt National Park, ND | 75 | >2 | Kirkpatrick et al. 1996 |

| Konza Prairie, KS | 74 | >3 | Towne 1999 |

| Witchita Mountains, OK | 72 | >2 | Shaw & Carter 1989 |

| National Bison Range, MT | 67 | >2 | McHugh 1958 |

| Catalina Island, CA | 67* | >3 | Duncan et al. 2013 |

| Hidden Valley (YNP) | 64 | >2 | McHugh 1958 |

| Henry Mountains, UT | 62 | >3 | Van Vuren & Bray 1986 |

| Northern Range (YNP) | 53 | >2 | Kirkpatrick et al. 1996 |

| Henry Mountains, UT | 52 | >3 | Van Vuren & Bray 1986 |

| Witchita Mountains, OK | 52 | >2 | Halloran 1968 |

| Mary Mountain (YNP) | 43 | >2 | Kirkpatrick et al. 1996 |

| Catalina Island, CA | 42 | >2 | Sweitzer et al. 2003 |

| Catalina Island, CA | 35 | >3 | Lott & Galland 1987 |

| Wood Buffalo National Park, NWT | 32 | >3 | Carbyn et al. 1998 |

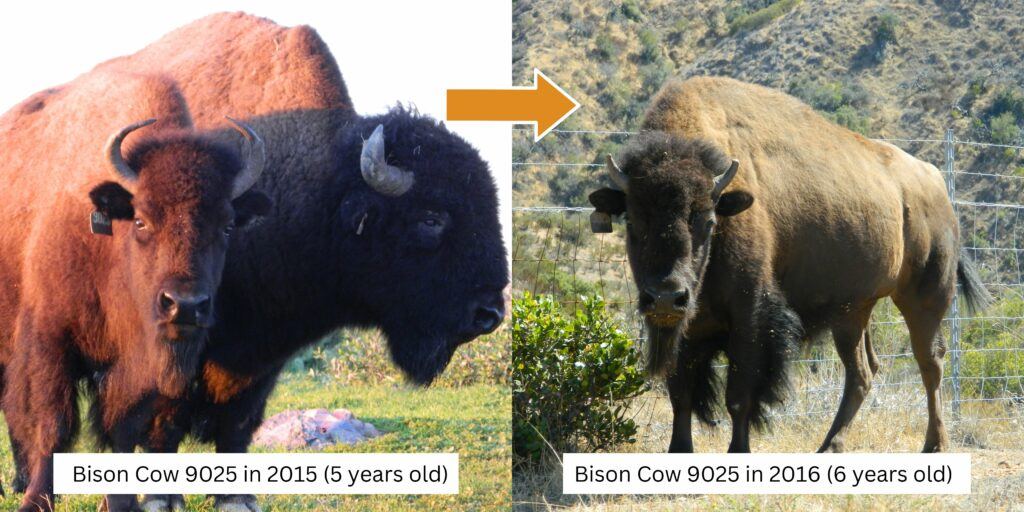

Bison on Catalina Island are Significantly Smaller than Mainland Bison

Within their report and subsequent manuscript, Sweitzer et al. noted that bison on Catalina Island are significantly smaller in body mass than mainland bison occupying prairie and mountainous rangelands, likely due to nutritional stress.

Genetic analysis conducted in 2004 resulted in the detection of cattle gene introgression in 45% of the Catalina Island bison herd and the recommendation that bison from Catalina not be used to supplement mainland herds that have no historical or genetic evidence of hybridization.

In a follow-up study, researchers assessed the phenotypic effects of domestic cattle DNA in American bison by comparing the weight and height of bison with cattle or bison mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from Santa Catalina Island, California (U.S.A.), a nutritionally stressful environment for bison, and of a group of age-matched feedlot bison males in Montana, a nutritionally rich environment.

While cattle gene introgression certainly plays a considerable role in influencing the size of the bison on Catalina Island, the contrast between individuals in nutritionally rich and nutritionally poor environments is dramatic.

Brittle and Broken Horns – Another Sign of Nutritional Stress

Horns are composed of a bony core covered with a sheath of keratin, and layers of keratin are added as the animal ages. Both male and female bison grow horns, and horn development and wear can be used, in most places, to estimate an individual’s age.

The horns on bison bulls are thicker at the base and tend to grow out and then upwards, while the horns on bison cows are thinner and begin to curl back toward their head after they reach three years of age. Horn wear, which results in the rounding and shortening of the horns, varies among individuals but is generally not significant until after 10-12 years of age.

Nutrition plays a significant role in the strength and development of an animal’s horns, and brittle, prematurely worn, or broken horns are good indicators of nutritional deficiencies and poor overall health.

While assisting in the managment of the bison on Catalina Island and conducting research for over a decade, we found that most of the bison had prematurely worn and broken horns, which often led to an overestimation of age.

In an attempt to quell concerns about the health of the bison on Catalina, prior leadership at the Conservancy frequently claimed that the bison on Catalina were “healthy and happy” and that they actually lived longer than bison occurring elsewhere. The truth of the matter is that the bison on Catalina are frequently in extremely poor health, and as a result, they just look older.

Frequent Observation of Emaciated Bison on Catalina Island

Advanced age in bison on Catalina Island is certainly a contributor to the observation of emaciated individuals, particularly in the absence of predators. However, prime-aged bison also struggle to survive on Catalina during extreme and persistent drought conditions.

Despite continuous recommendations to provide consistent feed, water, and mineral supplements, as is done for livestock throughout California, the Conservancy has chosen to promote the perception of a wild bison herd rather than address the poor condition of their animals.

Bison in their native range on the mainland experience considerable shifts in body weight as they bulk up during the summer and fall in preparation for winter, then fast for extended periods and occasionally munch on grasses, sedges, mosses, or lichens buried under the snow or hanging from the trees. Bison have adapted over thousands of years to this cycle.

On Catalina Island, forage is available all year round; however, by mid-summer through the fall, the forage is dry, brown, and nearly devoid of nutrients. The bison put energy into grazing and digestion but receive little nutrition in return.

Another key difference is that good or adequate conditions do return every year for bison within their native range, and they can often move or migrate to areas with better resources (not always the case). Drought conditions on Catalina Island can and have persisted for several consecutive years, providing no seasonal reprieve for the bison.

It is important to understand that by the time hip bones and ribs are visible to this degree, the animal is starving. Although the Conservancy has provided supplemental feed on occasion, it is usually done ad hoc (no measurable benefit) and generally only in response to public outcry associated with the observation of starving bison.

Ignored Management Recommendations

I am uncertain what the Conservancy’s current administration has in store for the bison on Catalina Island. However, in my opinion, prior administrations have disregarded and even silenced information pertaining to the poor health of the bison on the island and have dismissed the managment recommendations provided by experts.

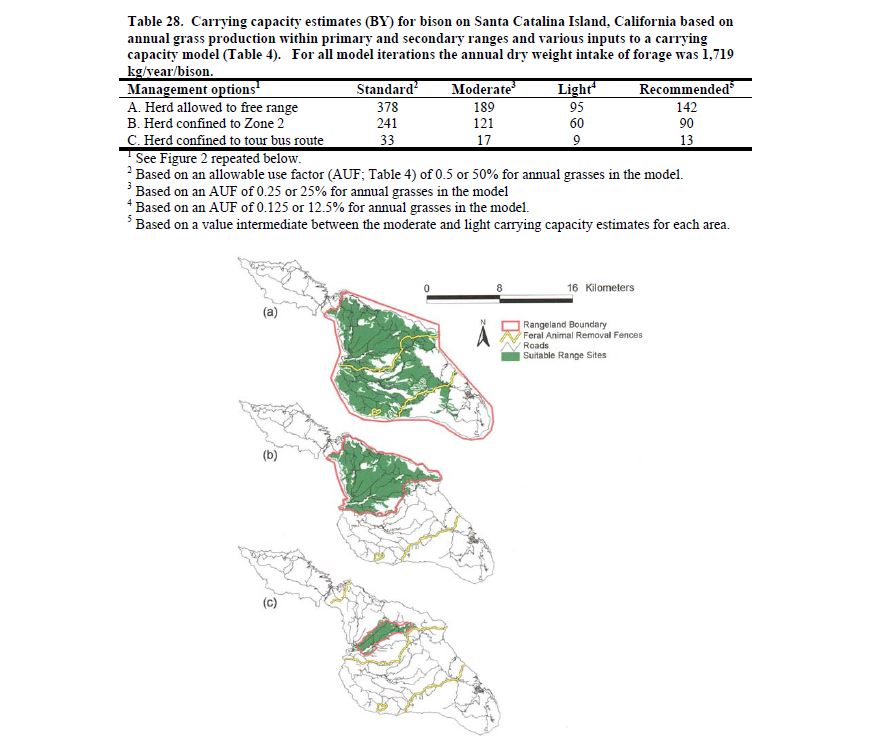

In their report, Swietzer et al. outlined three stocking strategies for the bison on Catalina Island. It is important to note that Sweitzer’s team was instructed not to explore the option of removing all of the bison from the island.

If the bison were to continue to range within their current area (nearly the entire eastern side of the island), Sweiter et al. recommended a stocking number of no more than 142 individuals. If restricted to zone 2, an area delineated within the study, no more than 90 individuals, and if restricted to a smaller area within zone 2 (a heritage herd approach), a stocking number of 13 bison was recommended.

In my opinion, this approach alone would not adequately address the bison’s poor health, and consistent supplemental feed and mineral licks would still be required.

In the end, the Conservancy did not adopt any of the recommended stocking options, and after a brief reduction in the herd through shipments to the mainland in 2003 and 2004, the herd was again permitted to expand to nearly 300 individuals by 2009.

Did the Use of Contraception Improve the Health of the Bison Cows?

The goal of the Catalina Island bison contraception program, initiated in 2010, was to hold the bison population at or below 150 individuals and give the cows a reprieve from the stress of pregnancy and nursing.

Although the program worked in halting reproduction, the bison were still permitted to range across the entire east end of the island, resulting in continued significant ecological impacts.

Often taking refuge in inaccessible areas of the island, the bison remained difficult to find by visitors and tours. Human safety remained an issue, with several visitors and residents being gored by bison, and due to a severe drought, one of the worst on record, that persisted from 2012 to 2017, the bison still struggled to survive.

Current Status of the Bison on Catalina Island

Today, approximately 90 bison remain on the island, and due to the persisting effects of the contraception vaccine, exacerbated by the poor condition and advanced age of the bison, no calves have been born since 2013.

Significant ecological impacts associated with the bison persist; visitors complain about not being able to consistently find the bison, and the Conservancy is currently in a lawsuit associated with a recent bison goring incident.

Future Management Options

I plan to address this topic in more detail in a future article. For the moment, however, I believe that there are only three appropriate managment options.

- Maintain a small heritage herd of 12-13 female bison within an enclosure along the primary interior tour route on the island, similar to the Bison Paddock in Golden State Park, and remove the rest from the island.

- Reinitiate the contraception program to ensure no additional calves are produced and allow the bison population to dissolve through attrition.

- Ship all of the remaining bison to Native American Reservations in South Dakota (same locations as before).

Each option has its challenges, pros, and cons, and there are various ways to approach each. However, I am hopeful that the current leadership at the Conservancy will choose to address the issue more appropriately than previous administrations.

Thank you for visiting WildlifeDetections.com. Check back often for new content or subscribe to my newsletter to receive updates on new articles. If you have enjoyed this post, please don’t hesitate to share.