75 Years of Deer Hunting on Catalina Island, California, Hasn’t Worked.

In response to the Catalina Island Conservancy’s plan to eradicate the introduced mule deer from the island, many people, most unaware of what efforts have been attempted previously, are demanding that hunting be used to manage the deer population instead.

A recent study, ten years in the making, confirms that hunting has not been a sufficient approach to curtail population growth, protect the unique ecology of the island, or even soften the extreme boom and bust cycles that result in deer overrunning the island after good rain seasons, and then starving to death during periods of drought.

To help forward the conversation productively, I have outlined details on the introduction of mule deer to Catalina Island, prior attempts to translocate deer off of the island, the current status of the mule deer population, how the Private Lands Managment (PLM) hunting program works, its limitations as a method to manage the deer population effectively, and the efforts put forth to increase harvest numbers through hunting over the last two decades.

The Introduction of Deer to Catalina Island

A book published in 1952 by the State of California Department of Fish and Game, A Survey of California Deer Herd: Their Ranges and Management Problems, outlines the introduction of mule deer to Catalina Island.

Longhurst et al. 1952

Santa Catalina Island – The deer population, incidentally, was derived from an initial stocking of 22 animals – a buck and two does from Modoc County, released in 1928, and 19 deer (mostly fawns) secured by Los Angeles County Officials and shipped to the island in the period 1930-32. The exact sex and age of the deer imported from Los Angeles was not recorded.

Side Note: The three deer introduced from Modoc County in 1928 were reportedly white-tailed deer, which apparently did not survive. The 19 deer Los Angeles County officials introduced in 1930-32 were mule deer.

The estimated number of grazing animals occupying the island in 1949 were:

- Wild goats – 10,000

- Wild Pigs – 5,000

- Deer – 2,000

- Bison – 60

- Total wild = 17,060

- Cattle – 600

- Horses – 200

- Sheep – 100

- Total Domestic = 900

Wild goats have shown that they are best fitted to compete in the dramatic struggle for forage. Wild pigs are nearly adaptable, and the deer prove to be a poor third. Yet the deer became numerous enough in the immediate vicinity of the town of Avalon to cause severe garden damage. Numerous complaints were registered with the Fish and Game Commission in 1947 and 1948, resulting finally in adoption of a cooperative plan for a controlled hunt of both sexes of deer in 1949.

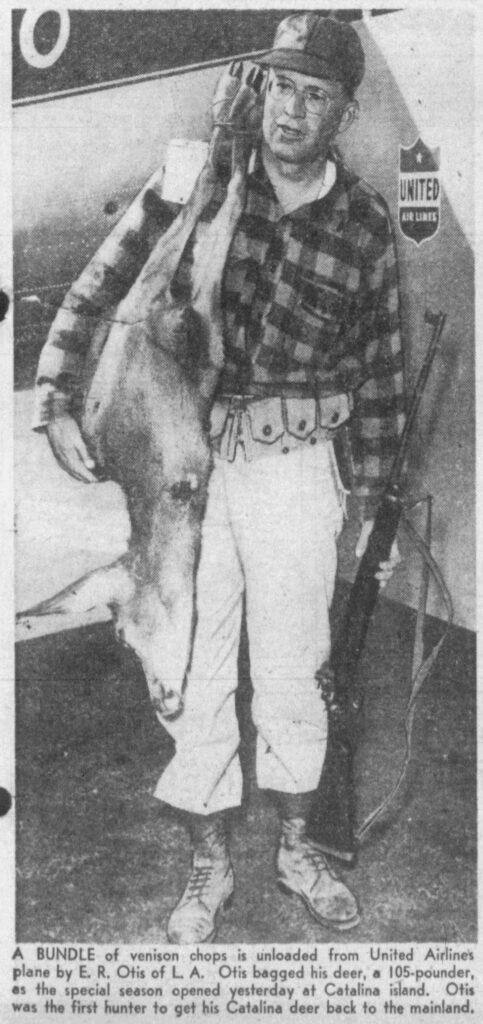

This historical event – the first antlerless deer hunt to be held in California – was successfully conducted between the dates of November 1, 1949, and January 31, 1950. Of 1,500 permits issued, 724 hunters actually reported, and they killed 477 deer, 231 of which were antlerless.

The hunt temporarily relieved the problem of deer damage, but there is little prospect of any productive managment of deer on the island until the excessive numbers of feral goats and pigs are reduced.

Cattle and sheep were removed from the island in the 1970s, goats, and pigs were removed in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the bison population has been maintained below 150 individuals through periodic removals and, more recently, contraception since 2010, a small number of horses remain at the Middle Ranch stables, and the deer population has ranged from 1,225 to 3,285 individuals since 2012. Sources – Ecosystems of California (2016), Duncan et al. 2017a, Duncan et al. 2017b, Duncan et al. 2013, and Stapp et al. 2022.

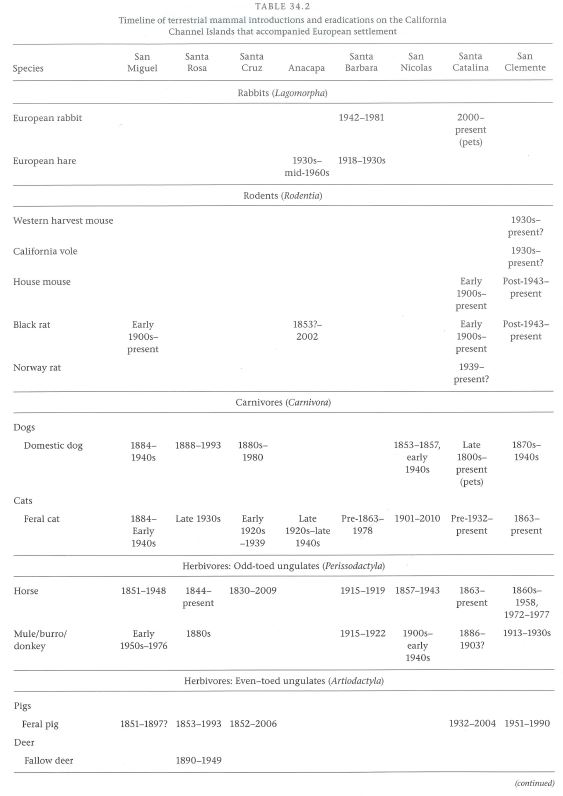

Timeline of Terrestrial Mammal Introductions and Eradications on the California Channel Islands

Source: Chapter 34 – Managed Island Ecosystems – Ecosystems of California (2016).

Attempts to Translocate Catalina Deer to the Mainland Failed Miserably

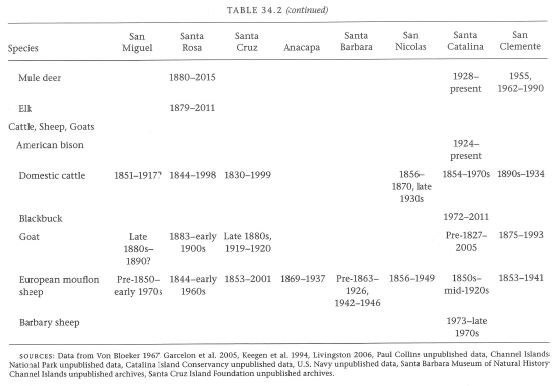

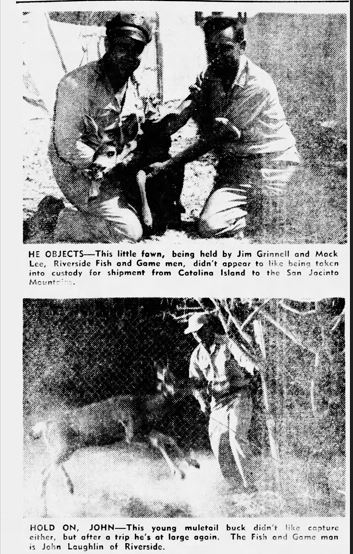

Hunting was not the first choice in managing the overabundant deer population on Catalina Island. In August 1948, the Catalina Island Company and the California Fish and Game Commission initiated efforts to translocate deer from the Island to the mainland.

Over three months, wardens captured 150 deer by luring them into high-fenced corrals with lettuce and alfalfa. The deer were roped, ear-tagged, loaded into stock wagons, and barged to the mainland.

Forty of the deer reportedly did not make it to the mainland. Several newspaper articles published at the time mention deer jumping over the corral fences during the capture process, and at least one article mentioned the loss of four fawns en route.

Little is known about how the deer fared post-release; however, I found an article about a mainland hunter who had harvested an ear-tagged Catalina deer despite regulations against doing so.

According to some sources, the goal of the translocation effort was to remove all 3,000 deer estimated to be on the island at the time. In contrast, others stated that the process would continue until the impacts of the deer were resolved.

The translocation effort was quickly abandoned due to the high costs, extensive efforts required, and the unlikely chance of success.

Although deer capture and immobilization techniques have improved considerably since 1948, so has our understanding of capture myopathy (an often fatal, exertion or stress-induced muscle degenerative condition affecting captured wild animals) and the commonly low post-release survival of translocated deer, particularly when released in areas dramatically different from where they originated (predators, vehicles, human development, etc.).

While the cost per animal translocated in 1948 was estimated to be $50-$60, more recent translocation efforts estimate the costs to range from $800 – $3,000 per deer and even higher as densities decrease and the deer become harder to locate. Tracking a subset of the translocated animals post-release would also likely be a requirement of this approach. This would add a considerable expense to the effort at $2,000 – $2,500 per GPS collar.

Other considerations include the potential to introduce new pathogens to the mainland deer population and the liability associated with deer conflicts (vehicle collisions, human injuries, crop or property damage) attributed to deer introduced to a new area.

Catalina Island Company Requests Ownership of the Deer (1948)

In response to the failed translocation effort and resistance towards initiating a hunting program, the Catalina Island Company proposed to purchase the deer from the state. If awarded ownership, the Island Company planned to round up and kill all but 500 of the deer and, according to M. J. Renton (an Island Company representative at the time), “dispose of the meat in any manner possible.”

Presumably, the Island Company then planned to utilize the same round-up and kill approach in perpetuity to keep the deer population at this arbitrary number.

Although this approach would have alleviated the burden on the Game Commission to manage Catalina’s deer population, there was concern that this precedence would lead to similar requests from other California islands where deer had been introduced.

Ironically, deer and all other introduced herbivores have since been eradicated from the other California Channel Islands after hunting, translocation, and contraception were determined to be insufficient management methods.

Deer Hunting on Catalina Island Continued for Decades

In response to continued interest in the opportunity to hunt deer on Catalina and the need to control the introduced deer population, hunting continued for several decades.

For many years, the program operated similarly to the initial 1949 hunt, albeit at a smaller scale. An article in the Valley Tribune outlining the process utilized in 1979 noted that 22 hunters were selected in a drawing, and each successful applicant could bring along two companions.

Led by Doug Bombard, the Catalina Hunting Lodge controlled the number of hunters and charged a fee that covered a guide for each hunting party, lodging, food, transportation in the field, and the dressing and packaging of deer for transport.

According to the article, success was virtually 100 percent, and an additional hunt targeting antlerless deer was also offered.

The Private Lands Management (PLM) Program on Catalina Island

In 1972, the Catalina Island Conservancy was founded and entrusted with managing approximately 88% of the island. Under its articles of incorporation, the Conservancy is legally mandated to protect Catalina Island’s native plants and animals, biological communities, and geological and geographical formations of educational interest.

Initiated as a pilot program in 1979 and expanded state-wide in 1983, the Califonia Department of Fish and Wildlife’s (CDFW) Private Lands Management Program (PLM) was designed to incentivize private land owners to make habitat improvements that benefit wildlife. In turn, qualified landowners could open their lands to hunters and charge fees for access.

Although not designed to control deer populations, the PLM program offered more flexible parameters, such as extended hunting seasons and the ability to harvest does, which were not permitted on public lands in California. The PLM program became the only option for the Conservancy to continue offering deer hunting on the island, and they joined the program in 1998.

PLM Deer Hunting Program Requirments

To qualify and maintain the PLM program on Catalina Island, the Conservancy must:

- Improve wildlife habitat by planting and protecting native plants, controlling invasive plants and animals, providing water resources, and supporting the recovery of threatened and endangered species.

- Submit an extensive management plan for approval every five years.

- Purchase PLM hunting tags from CDFW that can then be sold to hunters on the island.

- Conduct annual or near-annual deer population surveys.

- Recover tags, filled and unfilled, from every hunter that participates in the program. This effort has become so arduous that the Conservancy requires a $100 deposit to ensure tags are returned. In some instances, hunters have been prohibited from participating in the program after repeatedly failing to return their tags.

- Submit an annual report outlining the habitat improvement efforts completed during the year, deer population estimates, hunting efforts, harvest totals, and a tag request for the subsequent year.

Deer Hunting on Catalina Island – Three Types of Hunters

There are three groups of hunters on Catalina Island: residents, non-residents, and non-residents with a guide.

Resident hunters make up the smallest and least successful group. Only 30 residents purchased deer tags in 2021, and only 16 successfully harvested a deer. Some residents purchased multiple tags (2 per person is the limit in California), and a total of 26 deer were harvested by Catalina Island residents in 2021.

Seventy-one non-resident hunters purchased 116 Catalina PLM tags in 2021 and collectively harvested 69 deer. The number of non-resident hunters increased substantially in 2020 and 2021 after the requirement to be accompanied by a resident sponsor was removed. Other hurdles, including mainland parking, ferry transportation to the island, firearm storage, housing, and access to a vehicle for the interior, make it challenging for non-residents to participate in the Catalina hunting program.

Guided non-resident hunters comprise the largest group and have the highest success rate. Of the 217 tags purchased by guided non-resident hunters in 2021, 150 were filled (64%). Wildlife West Inc. has operated as the primary guide service on Catalina since 2003 and offers an exceptional hunting experience.

Like Catalina Island Land Tours and other private companies operating in the island’s interior, Wildlife West is an independent for-profit commercial organization operating under a lease agreement with the Catalina Island Conservancy. The Conservancy provides access to its land and some operational support (access to White’s Landing Camp, the Milk Shed for deer processing, and the use of Conservancy vehicles in some years). In turn, it receives a small portion of Wildlife West’s revenue.

A Wildlife West guided hunt includes travel to the island, accommodations, transport into the interior, field dressing and carry-out services, basic processing, and a return trip to the mainland. The cost of a 3-day hunt in 2023 was $5,500, and a 2-day hunt was $3,600, plus tag fees. Although this may sound expensive, these costs are comparable to guided deer hunts elsewhere in California and several other states.

In addition to Wildlife West, the Catalina Island Conservancy has offered a low-cost subsidized guided hunt service for several years. More details on this are below.

Summary of Tag Allotments and Deer Harvest Totals (2017 – 2021)

Each year, the Conservancy requests/receives a quota of PLM tags (500 in recent years) from CDFW. The Conservancy then communicates with Wildlife West and all resident and non-resident hunters who have participated in the program previously to determine how many tags may be needed for the year.

The Conservancy purchases PLM tags from CDFW in batches from the authorized quota to meet hunter interest. If the Conservancy purchases more tags than needed, it cannot return them to CDFW for a refund.

Hunters must first purchase a California deer hunting tag and then pay again to exchange it for a Catalina PLM tag once they arrive on the island. Essentially, CDFW gets paid twice per issued tag, and hunters forfeit their ability to hunt on the mainland if they are unsuccessful in filling their tag(s) on Catalina.

To clarify the terms used in the following table, the quota is the number of tags the Conservancy is authorized to purchase from CDFW, and issued tags are those purchased by hunters each year.

| Year | Tag Quota | Tags Issued | Bucks Harvested | Does Harvested | Total | Percent Tag Success |

| 2017 | 500 | 320 | 116 | 91 | 207 | 65% |

| 2018 | 500 | 340 | 114 | 109 | 223 | 66% |

| 2019 | 500 | 318 | 108 | 73 | 181 | 57% |

| 2020 | 500 | 339 | 117 | 104 | 221 | 65% |

| 2021 | 500 | 385 | 124 | 121 | 245 | 64% |

The Current Status of the Mule Deer Population on Catalina Island

Several mechanisms are used to assess the status of the introduced mule deer population on Catalina Island.

- Ecological resource monitoring, including assessments of endemic plant survival, enclosure-based studies, deer browse surveys, soil assessments, etc.

- Population monitoring via periodic (near annual) spotlight surveys.

- Hunting harvest totals and feedback from hunters and guides on hunting efforts, field observations, and the condition of animals harvested.

- Urban deer-related conflicts and concerns, including observations of sick, injured, or dead deer in Avalon or other human-populated areas, vehicle collisions, reports of impacts on personal or private property, and injuries associated with deer attacks.

A recent study published in the Proceedings of the Vertebrate Pest Conference (2022) outlines the current status of the introduced deer population based on ten years of spotlight surveys and harvest data. Key findings and recommendations from the study include:

- The population density of mule deer on Catalina Island, both island-wide ((10.2 per km2 (6.3-16.9)) and especially in Avalon (65.7 per km2 ), tends to be considerably higher than elsewhere in California.

- Given that deer are not native to Catalina, have no natural predators, and pose a threat to rare and endemic plants, they arguably should be considered overabundant on Catalina and managed as such.

- Because deer have remained abundant on the island over the last three decades, it does not appear that the Private Lands Management (PLM) hunting program has a meaningful effect on the deer population. By harvesting an average of 244.3 deer annually over the past ten years, hunters have taken only 13.0% of the estimated interior population in a given year. A much higher level of annual removal (e.g., 60% or more) is considered necessary to curtail deer population growth.

- Given 1) the costs associated with guided hunts, the challenge of convincing these hunters to focus their efforts on does (which would have the greatest impact), especially as hunter success rates decline with decreasing density, and 2) the logistical constraints imposed by the island’s inaccessible terrain and need to ferry gear to and from the island, it is not clear that public hunting will ever be sufficient to control the deer population.

- Other alternatives are currently impractical even if they were permitted legally (contraception) or are unacceptable due to capture myopathy and low survival (translocation).

- Given the continuing threats to the island’s natural resources posed by the deer and the Conservancy’s mission to preserve and restore the environment, a concerted eradication effort involving sharpshooting should be re-considered.

Efforts to Increase Deer Harvest Numbers on Catalina Island

Interestingly, many people demanding hunting be used instead of the proposed eradication effort have never hunted on Catalina Island or at all, for that matter, and have no understanding of how the process works or the challenges involved.

In this section, I will address some of the suggestions made to increase harvest numbers and manage the overabundant introduced deer population on Catalina Island through hunting.

Just Shoot More Does, Duh!

Due to the polygamous nature of deer, harvesting more females (does) is commonly recommended to reduce herd numbers. However, most hunters prefer to hunt bucks, and incentives or restrictions that force hunters to shoot does often don’t work.

Earn-A-Buck programs have been implemented in several states to manage overabundant populations of White-tailed deer. As the name implies, hunters must first harvest a doe and provide proof of their harvest before being permitted to hunt a buck.

As you might imagine, this program has been met with considerable resistance. Imagine investing all the effort required to go hunting only to watch a nice buck walk by, and you can’t shoot it because you haven’t filled your doe tag yet.

Add to this the requirement to abandon your hunt, drive 1-2 hours to town (Avalon) to provide proof of your harvested doe, and then return to the island’s interior to commence hunting. It should be evident that this program would not work on Catalina, particularly when considering the time and expense of getting to the island in the first place.

Over the years, the Conservancy has implemented various strategies to encourage hunters to harvest more does. Free antlerless tags have been offered as an incentive, and hunters who requested two PLM tags were sometimes required to harvest at least one doe. They didn’t have to harvest a doe first, but one of their tags could only be used to harvest an antlerless deer.

Efforts to push hunters to harvest does on Catalina have resulted in fewer hunters participating in the PLM program, fewer does being harvested, and fewer deer harvested overall.

Allow Hunters to Take More than Two Deer

The 2-deer per person per year limit is a California State law. The Conservancy has inquired about ways to adjust this restriction on Catalina, but there is no precedent for it and no clear process for making this change.

Catalina Island shares a hunting zone (D15) with portions of Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, and San Diego Counties, complicating the process further. The Conservancy has proposed isolating Catalina within its own hunting zone and then adjusting the regulations within the island-only zone, but no progress has been made on this front.

Would Allowing Hunters to Take More than Two Deer Make a Difference?

Due in part to the tag restrictions (forfeit mainland tags to purchase Island PLM tags) and the difficulty of transferring meat off the island on the ferry, many visiting hunters (guided and non-guided) currently only purchase one tag. In speaking to several hunting guides on the Island, I’ve also learned that, in many instances, only a fraction of each deer is salvaged due to the challenges of transferring the meat off the island.

Traditionally, a deer is shot, field-dressed, and then packed out. Once at the Milk Shed (a processing building utilized by Wildlife West), the head, skin, and legs are removed, and what remains is divided into smaller parts and fit into a cooler (a.k.a. ice chest). The hunter is then permitted one trip down the ramp at the ferry (sometimes two if it is not too busy) to carry all of their hunting gear, luggage, a deer head with rack (if they choose to keep it), and a cooler full of deer meat.

A more efficient strategy, particularly when hunting in difficult-to-access areas, is to salvage the prime cuts (backstraps, shoulders, rump, etc.) in the field and only pack out what would fit in a cooler in the first place. It should be noted that off-road vehicles such as ATVs or side-by-sides (SxS) are not permitted in the island’s interior, and due to the rugged cactus-riddled landscape, they wouldn’t be much use anyway. Every deer has to be manually packed out.

Allowing hunters to take more than two deer would potentially benefit resident hunters; however, with only 30-40 residents participating in the PLM program each year, it would not likely make much of a difference. It is also well-known that some resident hunters have been unlawfully taking more than two deer.

Extend the Deer Hunting Season – It’s Already the Longest Season in the US

South Carolina is often recognized for having the longest deer hunting season in the country. Within SC’s Lowcountry and Midlands areas, hunters can harvest deer from August 15 to January 1. The deer hunting season on Catalina Island commonly spans from July 13 to December 26, approximately two weeks longer than in South Carolina.

While there are some restrictions, for instance, in 2023, bow and crossbow were permitted in all zones on the island beginning on July 13, but rifle hunting was restricted to section A due to the high tourist season and safety concerns. Wildlife West had exclusive hunting access from September 16 to November 21 and maintained exclusivity in Zone 1 from November 22 to December 12. Hunting was open to all users in zones 2, 3, and 4 from November 22 to December 12 and in all zones from December 12 to 26.

High ambient temperatures, fawns with does, and bucks with not yet fully developed antlers would prevent people from hunting in early spring and summer, so starting the season earlier would not likely increase harvest numbers.

The Conservancy has considered expanding the season into January; however, seasonal rains and PLM reporting requirements (all tags must be reported to CDFW by December 31st) complicate this approach.

Winter storms frequently disrupt the ferry schedule and close interior roads. The Conservancy already incurs additional efforts and expenses in repairing roads rutted by hunters, reclaiming areas where hunters have driven off-road, and rescuing hunters who get stuck.

Offer More Hunting Guide Services and Make them Less Expensive

In response to the 2007 and 2008 fires on Catalina Island and concerns that deer would target rare, native, and protected plants resprouting in the burn areas, the Conservancy invested hundreds of thousands of dollars to erect fences around sensitive areas and expand the deer hunting effort.

In addition to Wildlife West, the Conservancy provided a subsidized guide service, which offered similar services but at less than half the price. The Conservancy’s guides focused heavily on harvesting does and reducing deer densities near the burn areas. During this time, residents were also provided with PLM tags for free.

The Conservancy postponed or canceled volunteer groups and internships and turned away visiting researchers to make room in their bunkhouse, volunteer camp, and intern housing for visiting hunters. Vehicles previously assigned to other projects were shifted to the deer hunting program, and new staff were hired or transferred from other positions to assist in implementing the guide service.

Conservancy staff and guides traveled to hunting/gun shows throughout the state to promote deer hunting on the island, and the program was heavily marketed on various platforms. In preparation for the surge in hunting activity, the Conservancy requested 700 PLM tags from CDFW in 2007 and 2008.

It Didn’t Work

Although it got off to a decent start, the investment ultimately did not pay off. In 2007, 547 PLM tags were issued to hunters, and 402 deer (117 Bucks, 285 does) were harvested. Although this was not the most deer harvested on the island in a single year (1949 = 477), it was the largest annual harvest of does.

Despite similar efforts in 2008, hunter interest waned. Of the 700 PLM tags available, only 372 were issued to or collected by hunters, and only 254 deer (120 bucks, 134 does) were harvested.

Hunting pressure, combined with the drought and fires (>10% of the island had burned), substantially reduced the deer population (2009 estimate = 609 deer). However, many deer remained in poor condition, and even in reduced numbers, they continued to significantly impact native, endemic, and protected plants, particularly within the burn areas.

Due to the poor condition of the deer and the increased effort required to fill tags, Wildlife West suggested pausing the hunting program to allow time for the deer numbers to rebound and bucks to mature. Needing to relieve the impacts on the environment, the Conservancy persisted, and the hunting program continued.

Despite the continued hunting pressure, the deer population more than doubled by 2011. In response to average and above-average rainfall years, the deer population has ranged between 1,225 and 3,285 individuals since 2012, and the hunting program has had little to no impact.

| Year | Tag Quota | Tags Issued | Bucks Harvested | Does Harvested | Total | Percent Tag Success |

| 2006 | 500 | 263 | 117 | 118 | 235 | 89% |

| 2007 | 700 | 547 | 117 | 285 | 402 | 74% |

| 2008 | 700 | 372 | 120 | 134 | 254 | 68% |

| 2009 | 500 | 286 | 79 | 137 | 216 | 75% |

| 2010 | 500 | 271 | 60 | 120 | 180 | 66% |

Conservancy Supports Local Hunters and Wounded Warriors

To encourage residents to participate in the PLM hunting program, the Conservancy partnered with the local Sheriff’s office in Avalon several times to provide on-island Hunter Education training, a requirement for new hunters wanting to purchase a hunting license in California. As Certified Hunter Education instructors, Conservancy guides could also countersign filled tags, another requirement of the PLM program.

In partnership with the local Sheriff’s office, the Conservancy also assisted in offering guided hunts in association with the Wounded Warrior Project. This is a fantastic program; please consider supporting their efforts by donating here.

Other Strategies Investigated

To increase access to the interior, the Conservancy investigated the option of providing a dedicated shuttle service for local and visiting hunters, but it didn’t pencil out financially or logistically.

The concept seemed simple enough: Maintain a reservation service to determine the number of drivers and vehicles (preferably trucks) required each day. Set a pickup location in Avalon to collect hunters before dawn and shuttle them to predetermined dropoff points in the interior. Then, pick them up at a set point later in the day.

Since cell phones, and to a large degree even radios, don’t work in the interior of the island, coordinating when and where each hunter or group of hunters needed to be picked up became the largest challenge and would require shuttles to run almost continuously from dawn until dusk. Even if only offered for a few weeks or months during the year, this would require multiple dedicated staff, the purchase and maintenance of additional vehicles, and other equipment such as radios and/or satellite trackers.

Even if a moderate fee were charged, providing the most basic shuttle service would have cost the Conservancy hundreds of thousands of dollars to initiate and maintain each year. Based on the interest of local hunters and estimates of how many more hunters may have participated in the hunting program if this service were offered, it wouldn’t have made a significant enough difference in deer harvest numbers to justify the expense.

Other ideas, such as providing a dedicated campground for hunters and a processing service, were also investigated but determined to be expensive and impractical.

Deer Hunting on Catalina Does Not Make Money

Due to its negligible impact on the deer population, the extensive time investment, and financial expense, the Conservancy has considered ending the PLM program several times in recent years. Contrary to popular belief, the deer hunting program on Catalina Island does not generate money for the Conservancy and offers no significant contribution to the island’s economy.

The annual income (approximately $50,000) generated through the guide service lease and membership dues does not offset the expense of managing the PLM program on Catalina Island. Requiring all hunters to utilize the guide service, as had been done in the past, would alleviate a considerable amount of the operating expense and likely result in an increase in the harvest numbers, but the Conservnay has remained committed to supporting residents interested in participating in the program.

Visiting hunters commonly stay with friends or family on the island or utilize the guide service, which provides meals and accommodations (hotels, restaurants, or other island amenities are rarely used). Guns and ammunition are not sold on the island, and the sale of California hunting tags and Catalina PLM tags goes directly to CDFW.

To put it in perspective, a weekend running event hosted by the Conservancy generates several times more income for the Conservancy and the Island than the six-month deer hunting season.

| Income Generated Annually | Annual Expenses (Conservancy) Associated with the PLM Program |

| Wildlife West lease (approx. $40,000 annually) | Added insurance costs to permit firearms and hunting on Conservancy land. |

| Membership dues ($35 per person). Approximately $7,000 – $10,000 | PLM 5-Year Plan – Requires numerous staff at all levels over multiple weeks/months. |

| Excess PLM tags not purchased by hunters are not refundable. | |

| Annual/near-annual deer population surveys require multiple weeks of planning, four crews of four staff (16 people), four trucks, multiple nights to conduct the survey, and a consultant to complete the data analysis. Each survey effort costs over $20,000 in staff time, fuel, equipment, and other expenses. | |

| Tag recovery and harvest data management require multiple dedicated staff for several weeks/months each year. | |

| PLM Annual Report – Requires numerous staff at all levels over multiple weeks. | |

| Increased ranger and facility efforts to manage hunters who damage roads during inclement weather, access unauthorized areas, drive offroad, get stuck, or break down. | |

| During the years the Conservancy offered a subsidized low-cost guide service, many staff were required to manage reservations, plan travel, coordinate and maintain housing, and guide hunters. Housing and vehicles were dedicated to this service, and other activities and projects were put on hold to support this effort. |

Very Few Residents Hunt Deer on Catalina Island

“Let the resident hunters take care of the deer problem” is a statement often made when sharpshooting efforts are proposed to manage deer populations in the US. Despite efforts to support resident hunters on Catalina Island (free PLM tags during some years, a 6-month hunting season, a subsidized low-cost guide service, on-island hunter safety training, and interior access behind locked gates), very few residents actually participate in the hunting program.

Deer hunting on the Island is not an essential cultural or traditional practice for most Catalina residents. For example, only 16 resident hunters harvested a deer in 2021 and 2022. On average, over the last decade, only 43 resident hunters bought tags (25 were successful) and harvested 41 deer per year.

Side Note: While working as a Wildlife Biologist on Catalina Island from 2004 to 2017, the Conservancy’s own Conservation and Facilities Department staff made up a significant proportion of Catalina’s resident hunters. The Conservancy also hosted an annual resident hunter meeting to provide updates on the PLM program and allow hunters to provide feedback. Zero and one hunter showed up to the meetings I attended.

Yes, some stipulations still make hunting on Catalina Island expensive, even for residents. For example, you must have liability, homeowner, or renter insurance (a requirement on other PLM programs in the state), purchase a Conservancy membership (a requirement for all users that access the interior of the island), and pay a refundable tag deposit (implemented due to the failure of many hunters to return their tags).

A single-day or annual interior permit is also required to drive a vehicle onto Conservancy lands. Again, this is a requirement for all users with vehicles entering the interior; however, those participating in the hunting program are allowed beyond locked gates, which are otherwise unavailable to other users.

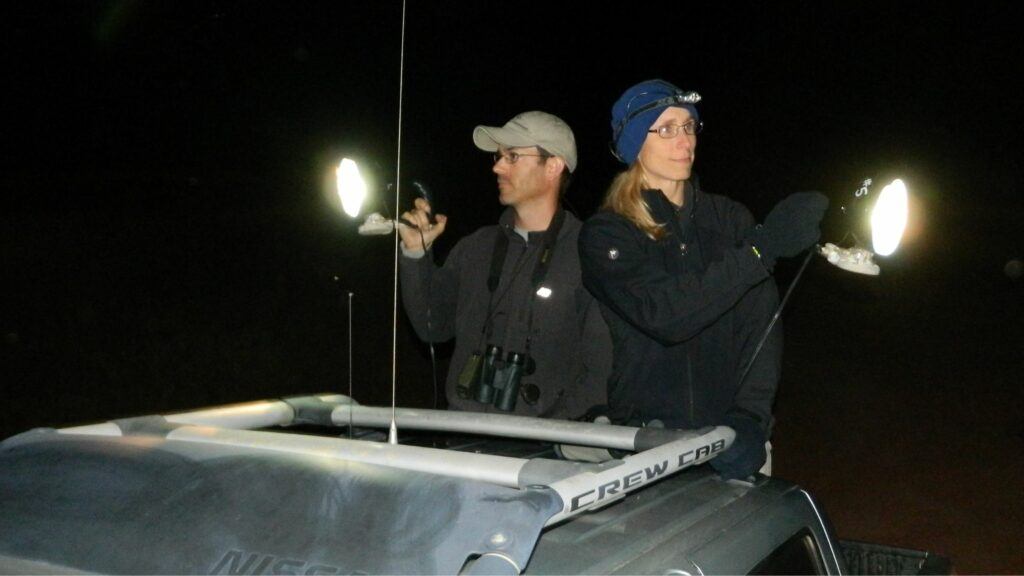

While island residents for 13 years, my wife and I (above) occasionally hunted deer on Catalina. Even though we lived in the interior, had our own vehicle (the price of fuel on Catalina often exceeds $6 per gallon), and had access to the Conservnacy’s milk shed (processing building) and disposal pit, the time commitment and expense associated with hunting on the island wasn’t worth it from a subsistence standpoint.

In response to claims that some residents rely on the deer meat or value the opportunity to hunt for themselves, the Conservancy proposed a subsidy program whereby residents who have participated in the PLM program in recent years would receive funds to be applied to the purchase of meat or other groceries or offset the expense of hunting on the mainland for some years following the eradication effort. Neither option was well received.

Sharp Shooting is More Humane than Hunting

Don’t get me wrong, I am an avid supporter of hunting, but the argument that hunting is somehow more humane than the Conservancy’s proposed eradication effort is absolutely false.

The American Veterinarian Medical Association (AVMA) and the American Association of Zoo Veterinarians (AAZV) define euthanasia as “the act of humanely killing animals by methods that induce rapid unconsciousness and death without pain or distress.”

With respect to free-ranging wildlife, a gunshot is an approved method of euthanasia. According to the AVMA, however, “A gunshot cannot be considered euthanasia in wildlife unless bullet placement is to the head.”

As noted within the AVMA’s Guidelines for Euthanasia, “For wildlife and other freely roaming animals, the preferred target area should be the head. It may, however, not be possible or appropriate to target the head when killing is attempted from large distances…A gunshot to the heart or neck does not immediately render animals unconscious, but may be required when it is not possible to meet the AVMA’s Panel on Euthasia’s (POE’s) definition of euthanasia.”

A Quick Comparison – Hunting VS Sharpshooting

| Hunting | Sharpshooting |

| Hunters almost exclusively target the vitals (heart and lungs), which does not immediately render the animal unconscious and does not meet the AVMA’s POE’s definition of euthanasia. | Sharpshooters commonly target the head to meet the AVMA’s guidelines for euthanasia. |

| Hunters’ skills can range from first-time beginners to avid hunters, likely resulting in more injured wildlife. | Sharpshooters are highly trained and experienced professional marksmen (often ex. military or law enforcement). |

| Many hunters are not physically able to pursue wildlife or track an injured animal in rugged terrain. | Sharpshooters must be physically capable and are authorized to use various tools and techniques to improve target accuracy and efficiently pursue injured animals to minimize suffering. |

| As a sport, hunting has limitations with respect to the tools and techniques that can be used. | Sharpshooters may be authorized to utilize various tools and techniques (helicopters, vehicles, baiting, traps, spotlighting, night vision and thermal scopes, sentinel animals, and higher capacity firearms) to improve target accuracy and efficiently pursue injured animals to minimize suffering. |

The American Association of Wildlife Veterinarians (AAWA) Supports the Conservancy’s Deer Eradication Plan

Please accept this note as the American Association of Wildlife Veterinarian’s (AAWV) unequivocal support for the Catalina Island Conservancy’s (CIC) Catalina Island Restoration Project; specifically, for the complete removal of mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) from Catalina Island, California…

Following an exhaustive investigation assessing the benefits and costs of various removal methodologies; e.g., the installation of fencing, recreational hunting, the introduction of predators, translocation, and reproductive management, the CIC’s informed conclusion to employ lethal removal via aerial sharpshooting has the support of the AAWV. This method of lethal removal is time-tested in the field of wildlife management, and affords the CIC the greatest opportunity to achieve total extirpation of mule deer from Catalina; especially in the context of animal welfare, human safety, efficiency of resources, and time management. It is the express view of the AAWV that the CIC’s mule deer removal plan is scientifically wellgrounded, informed, safe, humane, and urgently needed.

Sincerely, John A. Bryan, II, DVM, MS

President, American Association of Wildlife Veterinarians

By the Numbers

When it comes to introduced or invasive species management approaches, Animal rights organizations often prefer eradication efforts over hunting for all of the reasons mentioned above and because fewer animals are ultimately injured and killed.

Hunting, as a population managment tool, is the perpetual slaughter of animals, while eradication is one-and-done. Considering an average harvest of approximately 240 deer per year since the initiation of the Catalina Island PLM program 25 years ago, more than 6,000 deer have been killed, hundreds have likely been injured, and thousands have starved to death during periods of extreme drought.

Expand that average to the 75 years in which deer hunting has occurred on the island, and it becomes clear why eradication efforts are preferred over perpetual hunting. Organizations like the British Columbia Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (BC SPCA), for example, also acknowledge the need to remove introduced and invasive species when they threaten the survival of other animals or ecosystems.

Important Notes – The Catalina Island Conservancy is not a government organization; its lands are not public lands, and public tax dollars do not fund it. While allowing public access is required through the LA County Open Space Easement Agreement, the Conservancy’s primary purpose and legal mandate is to protect Catalina Island’s native plants and animals, biological communities, and geological and geographical formations of educational interest.

The opportunity to hunt deer on Catalina Island for the last 50 years would not have been possible without the Conservancy’s willingness to participate in the Private Lands Management Program and open its lands to hunting activities.

Conclusion

It is without question that Catalina Island offers a unique opportunity to hunt deer in California, and many hunters have enjoyed this experience over the last 75 years. It should be evident, however, that hunting has not been and will never be an adequate tool to effectively reduce or manage the introduced deer population on the island.

Despite significant investment, averaging only a 13% annual harvest of the estimated interior deer population has little to no impact, and no adjustment in the process (more tags, more deer per hunter, longer hunting season, lowered expenses, etc.) has or will be enough to reach the consistent 40% – 60% harvest rate required to curtail the population.

The only times the annual deer reduction came close to this goal were in 2007 and 2008, during extreme drought and after more than 10% of the island had burned. This reduction was not achieved through hunting alone; many deer starved to death during these years.

After an average rainfall year, even with persistent hunting pressure, the deer population more than doubled by 2011 and increased to over 3,000 individuals at times since 2012. Given this outcome, it should also be clear that even if a significant reduction in the deer population were achieved through some means, hunting would not be an effective approach to keeping the population down.

To summarize, the Catalina Island Conservancy’s PLM program offers, or has offered:

- The longest deer hunting season in the country

- The ability to hunt either-sex deer

- Free antlerless PLM tags and free PLM tags for residents

- A subsidized low-cost guide service in addition to a commercial guide service

- On-island hunter education training for residents (a requirement for new hunters wanting to purchase a Califonia hunting license).

- Interior island access behind locked gates, where other user groups cannot go.

Hunting has never proven effective in managing introduced ungulates on islands. An eradication effort, as proposed, is the most efficient and humane way to eliminate the impacts of the introduced deer population on Catalina Island.

Sharp shooting efforts, both aerial and ground-based, are currently being used successfully and safely worldwide to manage overabundant deer populations. Ungulate eradications using similar techniques have been used successfully on all of the other California Channel Islands and even previously on Catalina Island.

The Conservancy has conducted its due diligence and consulted experts from around the world to find a solution to the introduced deer issue on Catalina Island. Other management approaches, including contraception, translocation, and fencing, have been thoroughly investigated and found to be impractical, unfeasible, inhumane, and incapable of solving the problem.

Have you hunted deer on Catalina Island? What was your experience? Do you have other questions about the deer hunting program on Catalina? Has this article helped you understand the unique challenges of hunting deer on Catalina Island? Please consider sharing your experience by commenting below.

Thank you for visiting WildlifeDetections.com. Check back often for new content or subscribe to my newsletter to receive updates on new articles, and if you have enjoyed this post, please don’t hesitate to share.

What “damage” are the deer doing to the island? What percent of the natural vegetation has been harmed? Is it 1% or 99% ect..

Hi TJ. Thank you for your question. I will try to address it more thoroughly in a future post. The impact of the deer on Catalina island is not assessed as a “percentage of natural vegetation harmed” but rather impacts on certain plant species (particularly native, endemic, threatened or endangered species for which the Conservancy is mandated to protect – State and Federal protections), and the impact of the deer on the entire system (increased fire risk, transition towards more invasive species, climate resilience, erosion, tick born disease spread, etc.). The largest native herbivore on Catalina is the endemic ground squirrel, so the impacts of non-native grazers/browsers such as cattle, horses, bison, goats, pigs, and deer on the island have been extensive. Many of the endemic plants on Catalina Island have not evolved with deer, and have not developed natural defenses such as thorns or tannins making them hyperpalatable and specifically targeted by the deer. Since these plants occur across the island, there is no way to effectively fence them from the deer. Even a small number of deer left on the island would continue to disproportionately target these endemic and protected species. As the deer population booms and busts in response to periods of increased rain, and drought (which are becoming more frequent and severe), their impacts can become even more severe, and many of the deer starve to death. As demonstrated in Hawaii last year, the presence of deer also contribute to increased fire risk by shifting the fuel towards fast burning nonnative grasses, and their presence on the island prevent the entire system from becoming more resilient to climate change. Although the island has improved considerably since the removal of cattle, pigs and goats, the bison and the deer continue to cause considerable harm to the ecosystem. Studies have shown that after a system is severely impacted, as is the case with Catalina Island, even a small number of large nonnative herbivores can prevent its recovery. This is not an isolated case. Nonnative herbivores such as deer have been or are in the process of being removed from islands across the globe. It is unanimously supported by scientists and conservationists, and the process of using sharpshooters is supported by wildlife veterinary organizations and most animal rights organizations. Thank you again for commenting.

Disappointing to see so many obscure arguments used to invalidate the hunting opportunity of the island. Some of those statistics were relevant, but many are just fluff used by the conservancy to further their ideas. 90% of this problem will never make sense to the average person who has never participated in this hunt and culture of the island. It is truly a unique experience found nowhere else on the planet! It is what it is. At the end of the day, the only ones to gain from this are the eradication companies. We all lose something through this decision.

Hello Anonymous. Hunting deer on Catalina is a unique experience, but one could argue that every experience on Catalina Island is unique. Deer hunting is available in almost every part of North America, and each place offers a unique experience. My intentions in writing this article were not to invalidate the hunting opportunity, but to clarify that it is an ineffective tool in managing an invasive species on an island with an entire ecosystem that is found “nowhere else on the planet”. I’m not sure which data you are referring to as “fluff”. We used 10 years of spotlight surveys to monitor the deer population and recorded harvest data. The deer population on the island booms and busts with rainfall, and hunting has had little to no impact. With fewer than 40 island residents participating in the program annually, I do not agree that deer hunting is a cultural part of the island. That being said, the Conservancy has recently announced it’s plans to continue offering residents the opportunity to hunt on the island. You may not agree with the Conservancy, and I don’t agree with them on many things; that is why I left. They are mandated to protect native species and the island’s unique ecology, not run a hunting camp. You condemn the Conservancy for “furthering their ideas” on land they privately own, but don’t seem to appreciate the fact that the opportunity to hunt deer on the island for the last five decades has been provided by the Conservancy.